Building a Pull Request bot with Azure Functions - Part 2 - How it works

- 13 minutes read - 2663 wordsThis is the second post in my series on building a pull request bot using Azure Functions. If you haven’t read my first post I strongly recommend doing so before diving into this post. Remember that this series is a part of the Applied Cloud Stories initiative.

In this post I’ll dive into the details of how the bot actually works, from receiving notifications from Azure DevOps to managing state and posting comments back to the pull request.

Receiving notifications

The first thing we’ll need for a pull request bot to work is to receive notifications when pull requests are created. Since we were using Azure DevOps (Server) we could use its Service Hooks feature to receive these notifications. Of course this could work with other systems as well, such as GitHub which has a similar feature. All these features are generally referred to as web hooks. Both Azure DevOps and GitHub will essentially do an HTTP POST request to an endpoint and will send along a payload containing the details of an event that has occurred. HTTP triggered Azure Functions are ideal for this. For example, this is the definition of the Azure Function that receives the pull request created event from Azure DevOps:

[FunctionName(nameof(PullRequestCreated))]

public async Task<IActionResult> PullRequestCreated(

[HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Anonymous, "post", Route = "pullrequests/created")] HttpRequest req,

[OrchestrationClient] DurableOrchestrationClientBase orchestrator,

ILogger log)

{

}

There are a couple of things to note here. First of all, you might notice that this isn’t a static method while most examples for Azure Functions use static methods. This is because we’re using dependency injection which requires an instance of class to be created in order for the dependencies to be injected.

The other thing you might notice is that we’re using AuthorizationLevel.Anonymous, which means that anybody can execute this function. That doesn’t mean that we don’t do any authentication, but we’ve implemented it as part of the function itself. The request body contains a subscription identifier which is the identifier of the service hook in Azure DevOps. We’ve configured the bot with a set of subscription identifiers that are allowed, and deny requests that either do not have a subscription identifier or if the identifier is not in the list of authorized identifiers. In hindsight we could have used AuthorizationLevel.Function instead, which uses a key that we could have configured on the Azure DevOps side, which made the overall configuration a little bit easier. Never too late to change it I guess.

Next step was to actually do something with the payload. As it turns out, Microsoft has a web hooks library with the definitions of all the payloads that Azure DevOps posts to your endpoint. That makes it a lot easier to deserialize the request body into something we can use. It contains among other things the pull request that has been created, who created it, the subscription identifier that triggered the event being posted, etc.

Of course we also want to run our validations again when the pull request has been updated so we added an additional HTTP triggered function which is almost the same:

[FunctionName(nameof(PullRequestUpdated))]

public async Task<IActionResult> PullRequestUpdated(

[HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Anonymous, "post", Route = "pullrequests/updated")] HttpRequest req,

[OrchestrationClient] DurableOrchestrationClientBase orchestrator,

ILogger log)

{

}

Finally we figured that while we were at it it makes sense to also run our validations whenever a build completes that was triggered as part of a pull request so that we can do additional checks on those builds as well. So we added yet another HTTP triggered function to do just that:

[FunctionName(nameof(BuildCompleted))]

public async Task<IActionResult> BuildCompleted(

[HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Anonymous, "post", Route = "builds/completed")] HttpRequest req,

[OrchestrationClient] DurableOrchestrationClientBase orchestrator,

ILogger log)

{

}

As you can probably guess by now all these functions have a similar implementation which revolves around the OrchestrationClient that is injected into each of those functions, which is the entry point for Durable Functions. Let’s dive in to see what happens there.

Orchestration

The orchestration is what maintains the state of the validations that have run for a pull request. When the pull request created function from above runs, it starts a new instance of the orchestration:

// Build the analysis context

var instanceId = payload.Resource.PullRequestId.ToString();

var pullRequest = new PullRequest

(

currentState: payload.Resource.Status,

pullRequestId: payload.Resource.PullRequestId.ToString(),

projectId: payload.Resource.Repository.Project.Id,

repositoryId: payload.Resource.Repository.Id,

repositoryName: payload.Resource.Repository.Name,

sourceRefName: payload.Resource.SourceRefName,

targetRefName: payload.Resource.TargetRefName,

created: payload.Resource.CreationDate

);

var context = new AnalysisContext(pullRequest);

// Initialize a new orchestration

await orchestrator.StartNewAsync(nameof(PullRequestFlow), instanceId, context);

As you can see in the code sample above we first create an object to represent the pull request, with some basic information that we get from the payload such as its state, the repository it has been created in, the source and target branches, etc. We then wrap that into an AnalysisContext (more on that later) and start a new instance of the PullRequestFlow orchestration with the context and give it an identifier that matches the identifier of the pull request. This is what the durable orchestration function definition looks like:

[FunctionName(nameof(PullRequestFlow))]

public async Task Run([OrchestrationTrigger] DurableOrchestrationContextBase context, ILogger logger)

{

// Get the AnalysisContext that is passed as input to this function

AnalysisContext analysisContext = context.GetInput<AnalysisContext>();

}

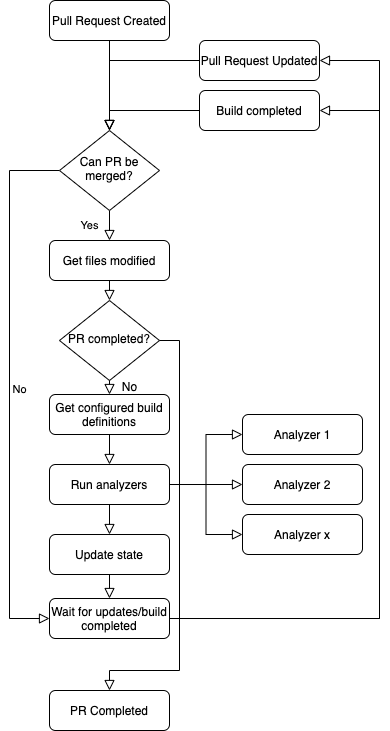

The pull request flow is a durable orchestration that will keep running until the associated pull request is completed. It doesn’t do much in and of itself, but delegates actual work to other functions and coordinates those. To give an overview of how this flow works we’ve drawn a diagram that shows each of the steps in the process:

Since most of the validations that we imagined early on that we wanted to do would revolve around the files changed in the pull request, we’ll first need to compile that list. To do that though, we need to ensure that the pull request is currently in a mergeable state. We’ll do this by calling out into an activity function (an Azure Function that does the actual work) like this:

var mergable = await context.CallActivityWithRetryAsync<bool>(nameof(EnsurePullRequestIsMergeable), _retryOptions, analysisContext);

We’re passing along the AnalysisContext to this function which includes the details of the pull request so we can use that to do a call into Azure DevOps to determine if the pull request is mergeable:

[FunctionName(nameof(EnsurePullRequestIsMergeable))]

public async Task<bool> EnsurePullRequestIsMergeable([ActivityTrigger] DurableActivityContextBase context)

{

// Get the pull request in question

var analysisContext = context.GetInput<AnalysisContext>();

var pullRequest = analysisContext.PullRequest;

// Check if the pull request is mergable

var result = await _gitClientService.IsPullRequestMergable(pullRequest.ProjectId, pullRequest.RepositoryId, pullRequest.PullRequestId);

return result.GetValueOrDefault();

}

Note that the call to the Azure DevOps API has been put behind an interface so that we could potentially swap that out for a different implementation that targets a different source control platform. We try very hard to keep the interface as platform agnostic as we possible can. So let’s go one level deeper and have a look at what’s happening behind that call in our Azure DevOps specific implementation:

public async Task<bool?> IsPullRequestMergable(string projectId, string repositoryId, string pullRequestId)

{

var client = await connection.GetClientAsync<GitHttpClient>();

GitPullRequest pullRequest = await client.GetPullRequestAsync(projectId, repositoryId, int.Parse(pullRequestId));

if (pullRequest.MergeStatus == PullRequestAsyncStatus.Queued)

{

// If merge status is queued we'll have to wait a bit for the merge status to be available, so we don't know yet

return null;

}

return pullRequest.MergeStatus == PullRequestAsyncStatus.Succeeded;

}

A fairly simple piece of code that makes use of the .NET Client library for Azure DevOps. To establish a connection to Azure DevOps we use a personal access token of an automation account that we’ve created specifically for this purpose.

Provided that the pull request is in a mergeable state, the next step is to determine the list of files that have been modified as part of the pull request. This is a separate activity function again which gets the AnalysisContext as input and uses the same abstraction as our previous function to call into Azure DevOps to get that list of files. This requires two steps, first we need to get the details of the pull request itself, get the last merge commit identifier from there and then get the details of that merge commit:

public async Task<List<string>?> GetChangedFilesInPullRequest(string repositoryId, string pullRequestId)

{

var client = await connection.GetClientAsync<GitHttpClient>();

// Get the full pull request details

var pullRequest = await client.GetPullRequestAsync(repositoryId, int.Parse(pullRequestId));

if (pullRequest.Status == PullRequestStatus.Completed)

{

// Pull request has already been completed in the mean time, nothing more we can do here

return null;

}

var mergeCommit = await client.GetCommitAsync(pullRequest.LastMergeCommit.CommitId, pullRequest.Repository.Id, 1);

var totalChangeCount = mergeCommit.ChangeCounts.Sum(changeCount => changeCount.Value);

if (totalChangeCount > 0)

{

var allChanges = await client.GetCommitAsync(pullRequest.LastMergeCommit.CommitId, pullRequest.Repository.Id, totalChangeCount);

return allChanges.Changes.Where(item => !item.Item.IsFolder).Select(item => item.Item.Path).ToList();

}

else

{

return new List<string>();

}

}

We then put this list of files on the AnalysisContext so that our validations can use that list to do their thing (more on that later). Because we wanted to also include builds into our validations we then collect a list of configured build definitions. This is configured in Azure DevOps by using branch policies, so we need to do some calls into the Azure DevOps API to get the information we need:

public async Task<int[]> GetConfiguredBuildsForPullRequest(string projectId, string repositoryId, string pullRequestId, string targetBranch)

{

// Get all policy configurations of type Build

var client = await connection.GetClientAsync<PolicyHttpClient>();

var policyConfigurations = await client.GetPolicyConfigurationsAsync(projectId, null, new Guid("0609b952-1397-4640-95ec-e00a01b2c241"));

// Find policies that apply to the provided repository and target branch

var policies = policyConfigurations.Where(p => p.Settings["scope"].Any(s =>

s["repositoryId"].ToString() == repositoryId &&

s["refName"].ToString() == targetBranch));

// Select the configured build definition identifiers of those policies

return policies.Select(p => p.Settings["buildDefinitionId"].Value<int>()).ToArray();

}

What’s happening here? We first have to get all the configured policies in the entire team project of a particular type, in our case build policies (represented by that GUID). We can then filter that set of policies down to the repository in which our pull request was created and the branch to which the policy applies which should be the target branch of our pull request. Once we have that policy we can get the associated build definition identifiers. Note that this can be more than one depending on how the policy is configured.

Running the validations

Now that we have all the information about the pull request that we need it is time to do our actual validations. We choose to do a pluggable approach here so that we could easily add and remove analyzers as we went along. We also choose to do a fan-out and implement each analyzer in its own activity function. This is also nice from a monitoring perspective, but more on that in a later post. Let’s have a look at how we handle the fan-out in our orchestration:

// Fan out and run each analyzer

var analyzerTasks = new Task<object>[PullRequestAnalyzers.Analyzers.Length];

for (int i = 0; i < PullRequestAnalyzers.Analyzers.Length; i++)

{

// Queue up the analyzer function

var analyzerName = PullRequestAnalyzers.Analyzers[i];

analyzerTasks[i] = context.CallActivityWithRetryAsync<object>(analyzerName, _retryOptions, analysisContext);

}

var results = await Task.WhenAll(analyzerTasks);

This is a typical fan-out pattern with Azure Durable Functions, we simply start each activity function and put the Task representing that function into an array. Then we await all of them. Once all of them have completed execution of the orchestration continues. Each activity function has pretty much the same implementation:

[FunctionName(nameof(MyPullRequestAnalyzer))]

public async Task<object> MyPullRequestAnalyzer([ActivityTrigger] DurableActivityContext context, ILogger logger)

{

var analysisContext = context.GetInput<AnalysisContext>();

var state = GetStateFromContext<MyPullRequestAnalyzer.StateBag>(analysisContext, nameof(MyPullRequestAnalyzer));

var analyzer = new MyPullRequestAnalyzer(logger, _gitClientService, analysisContext, state);

await analyzer.Analyze();

return state;

}

It gets the AnalysisContext as input, which includes a dictionary containing the state of each analyzer, where the key is the name of the analyzer and the value is an object. This allows each analyzer to define its own state bag which is just an object with some properties containing whatever state the analyzer needs. Here’s how we get that from the context:

private static TState GetStateFromContext<TState>(AnalysisContext analysisContext, string analyzerName)

where TState : class, new()

{

if (!analysisContext.AnalyzerStates.TryGetValue(analyzerName, out object state))

{

return new TState();

}

else

{

return JsonConvert.DeserializeObject<TState>(state.ToString());

}

}

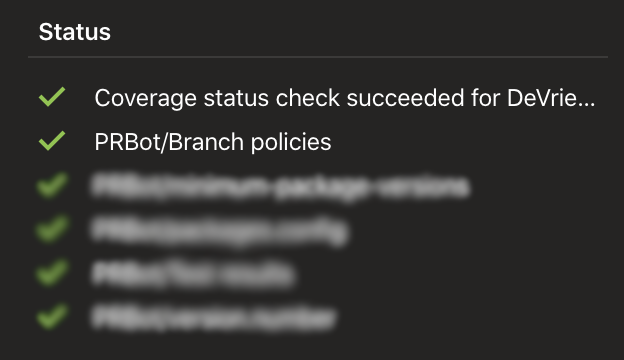

Once we have the current state for the analyzer we can go ahead and run the analyzer itself. Each analyzer inherits from the generic base class PullRequestAnalyzerBase<TState> which exposes properties for both the AnalysisContext and the TState for that analyzer. It also takes care of updating the state on the pull request itself, so that our developers can see that the analysis is running or if it has completed successfully or not.

From there, it’s basically up to the analyzer itself to determine what it wants to do and we’ve come up with different analyzers as we went along. They are mostly specific to our processes though. We do try to stick to using the abstractions I talked about earlier so that we could swap out Azure DevOps for something else without too much impact to the bot itself.

What’s more interesting though is what happens with the state of the analyzer once it has run. As seen in the code sample above each activity function returns the state of the analyzer. This is used by the orchestrator to update the state on the AnalysisContext. Here’s the piece of code that ensures that we update the state correctly:

var results = await Task.WhenAll(analyzerTasks); // We saw this line earlier

for (int i = 0; i < results.Length; i++)

{

var analyzerName = PullRequestAnalyzers.Analyzers[i];

analysisContext.AnalyzerStates[analyzerName] = results[i];

}

Waiting for changes

After all the analyzers have run we can wait for changes to be made to the pull request, or builds that are running to complete. We do this by waiting for external events to occur, another feature of Azure Durable Functions. These external events are triggered by the HTTP triggered functions for pull request updates and build completed that we already saw at the start of this post. Let’s have a look at how we handle these events in the orchestration:

var pullRequestUpdated = context.WaitForExternalEvent<string>(PULL_REQUEST_UPDATED_EVENT);

var buildCompleted = context.WaitForExternalEvent<(int buildDefinitionId, int buildId, string status)>(BUILD_COMPLETED_EVENT);

var completedTask = await Task.WhenAny(pullRequestUpdated, buildCompleted);

We start two tasks, one for each event that can occur and then use Task.WhenAny to wait for either one to complete, whichever one comes first. This returns the task that actually completed, so we can do an if check to see which of the events has occurred. In the case of a pull request updated event we receive the new state of the pull request (ie. completed, abandoned, etc.). If the new state is completed, we quit the orchestration. In all other cases we continue the orchestration as new, using the following code:

context.ContinueAsNew(analysisContext);

This will start the entire orchestration from the top, but with the updated AnalysisContext with all its state as the input. That means that the state of each analyzer is preserved. So for example, if the analyzer has posted a comment to the pull request, it can store the identifier of the comment in its state. When it runs again after an update has happened on the pull request it can check its state, find a comment identifier there and simply do nothing or close the comment if it has been resolved.

As for the build completed event, we mostly do the same thing. We receive the identifier of the build definition, the identifier of the build and the status of completed build, put that information on the AnalysisContext and then restart the orchestration in the same way as above. Analyzers can then choose to use that information to do their thing.

Conclusion

Wow, that was a lot. Yet, I still think this is a much simpler solution than what we had initially that I alluded to in my previous post. We just keep running the same loop over and over until the pull request is completed. By running each analyzer in its own activity function we also don’t have to worry about one of them blocking the others.

Of course this setup isn’t without its caveats either and we did run into a couple of things when we put this into production, but let’s talk about that in more detail in my next post.