Migrating existing .NET projects to SDK-based projects

- 8 minutes read - 1591 wordsIn my previous blog post I talked about sharing .NET code across the various .NET platforms we now have within the .NET ecosystem (.NET Framework, .NET Core, Xamarin). In that post I also showed the new tooling within Visual Studio 2017 that enables (among other things) cross-targeting a lot easier than it was before. Since then two new versions of the new tooling experience for .NET projects have been released, and things have matured quite nicely. It is still not RTM quality, but things have certainly improved quite a bit since my previous post. And with it, the csproj file we all know and love (or hate ;)) has become quite a bit smaller and more readable, especially when compared to the current tooling. For example, here is the entire csproj file that I get when I create a new class library using the “classic” tooling (albeit using Visual Studio 2017):

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<Project ToolsVersion="15.0">Debug</Configuration>

<Platform Condition=" '$(Platform)' == '' ">AnyCPU</Platform>

<ProjectGuid>10a6f289-0682-4624-9980-26adcf201d74</ProjectGuid>

<OutputType>Library</OutputType>

<AppDesignerFolder>Properties</AppDesignerFolder>

<RootNamespace>ClassLibrary1</RootNamespace>

<AssemblyName>ClassLibrary1</AssemblyName>

<TargetFrameworkVersion>v4.5.2</TargetFrameworkVersion>

<FileAlignment>512</FileAlignment>

</PropertyGroup>

<PropertyGroup Condition=" '$(Configuration)|$(Platform)' == 'Debug|AnyCPU' ">

<DebugSymbols>true</DebugSymbols>

<DebugType>full</DebugType>

<Optimize>false</Optimize>

<OutputPath>binDebug</OutputPath>

<DefineConstants>DEBUG;TRACE</DefineConstants>

<ErrorReport>prompt</ErrorReport>

<WarningLevel>4</WarningLevel>

</PropertyGroup>

<PropertyGroup Condition=" '$(Configuration)|$(Platform)' == 'Release|AnyCPU' ">

<DebugType>pdbonly</DebugType>

<Optimize>true</Optimize>

<OutputPath>binRelease</OutputPath>

<DefineConstants>TRACE</DefineConstants>

<ErrorReport>prompt</ErrorReport>

<WarningLevel>4</WarningLevel>

</PropertyGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<Reference Include="System"/>

<Reference Include="System.Core"/>

<Reference Include="System.Xml.Linq"/>

<Reference Include="System.Data.DataSetExtensions"/>

<Reference Include="Microsoft.CSharp"/>

<Reference Include="System.Data"/>

<Reference Include="System.Net.Http"/>

<Reference Include="System.Xml"/>

</ItemGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<Compile Include="Class1.cs" />

<Compile Include="PropertiesAssemblyInfo.cs" />

</ItemGroup>

<Import Project="$(MSBuildToolsPath)Microsoft.CSharp.targets" />

</Project>

Let’s compare that for a second with what I get when I create a new .NET Standard class library project using the brand new tooling:

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk">

<PropertyGroup>

<TargetFramework>netstandard1.4</TargetFramework>

</PropertyGroup>

</Project>

As you can see, the file has become a lot smaller out-of-the-box and it is much more readable as well. Most of the magic is happening through the Sdk attribute on the Project element. Hence I call these new projects SDK-based projects. No more ProjectTypeGuids to deal with, and no more including every single file causing merge conflicts when two team members have added a file to the project. All in all I think the new tooling is a great improvement, so I was curious to see if I could take an existing .NET project that uses the “old” tooling and migrate it over to the new SDK-based tooling. According to the release notes we might get such a migration path within Visual Studio sometime in the future, but I wanted to try it out now and write about my experience doing so, so here it goes.

Disclaimer

First of all, let me say that you should probably not do this for any application that you’re working on on a daily basis. This is highly experimental stuff and even if it works for you you’ll have to use Visual Studio 2017 to work with your code which isn’t quite finished yet. If you’re adventurous like me though, go ahead and try it out for yourself. Make sure you’re using some kind of version control (like Git or TFS Version Control) though so you can go back.

Attack plan

At a high level such a migration could look like this:

- Get all the projects in a solution

- For each of those projects

- Remove the existing .csproj file

- Generate a new csproj file using dotnet new

- Copy package references from packages.config

Of course, depending on the number of projects in a solution, this can become a bit tedious to do by hand. Therefore I wrote a PowerShell script that does these steps (and a few more due to some complexities of the solution I tried it on). Ive published the script on GitHub if you want to try it out. Pull requests are welcome ;).

The project

So far I’ve ran the script on one solution, making adjustments and then running it again (after undoing my changes). This solution consists of a regular .NET Framework (4.5.2) class library which contains most of the logic. On top of that there is a Windows service project (using NServiceBus) and an ASP.NET Web API project which don’t have much logic themselves, but use the logic from the core library. Of course there are also some test projects in there; a regular MSTest unit test project as well as a SpecFlow test project. Finally there are two more class library projects that include the same set of files, but one compiles for .NET Framework 4.5.2 and the other compiles for Silverlight 5.0 (yeah, I know). They contain some classes that are shared between our backend code (which is in this solution) and our front end (which is in a separate solution). In fact, the Silverlight project is exactly what motivated me into figuring out if we could migrate to the new project format. Visual Studio 2017 (which is currently an RC but should hit RTM soon) no longer supports Silverlight projects so as it stands right now we won’t be able to upgrade to VS2017 when it ships since we still have these Silverlight projects. And although we are moving away from Silverlight, we will have to deal with them for the time being. However, I found out that if we put the and elements with the right values for Silverlight into a project file using the new format, we can actually get the code to compile against Silverlight and all should be well. Of course, this isn’t a solution for our front end solution which has all the UI stuff, but it does solve the problem for our backend solutions that only contain a couple of simple classes.

In practice

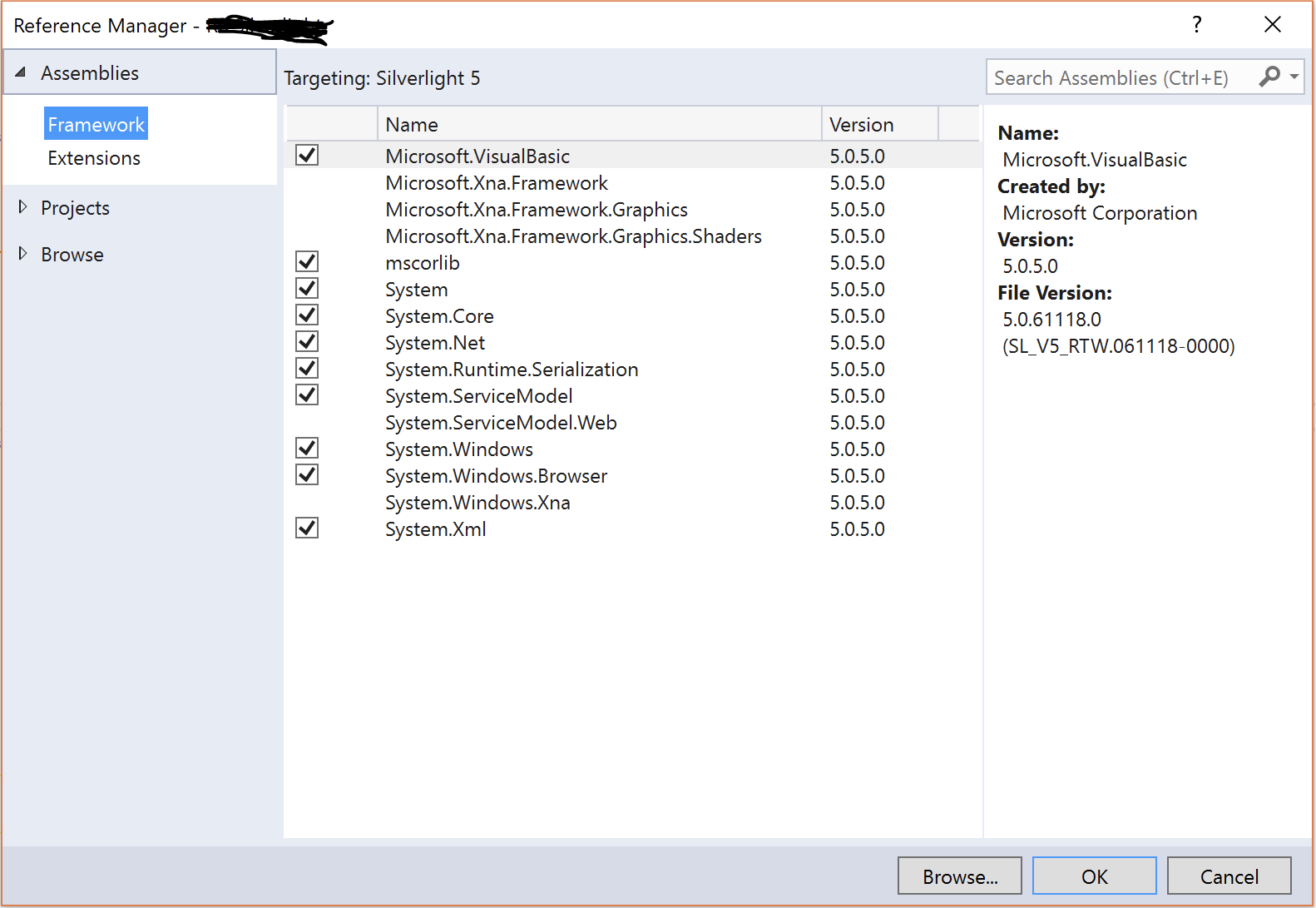

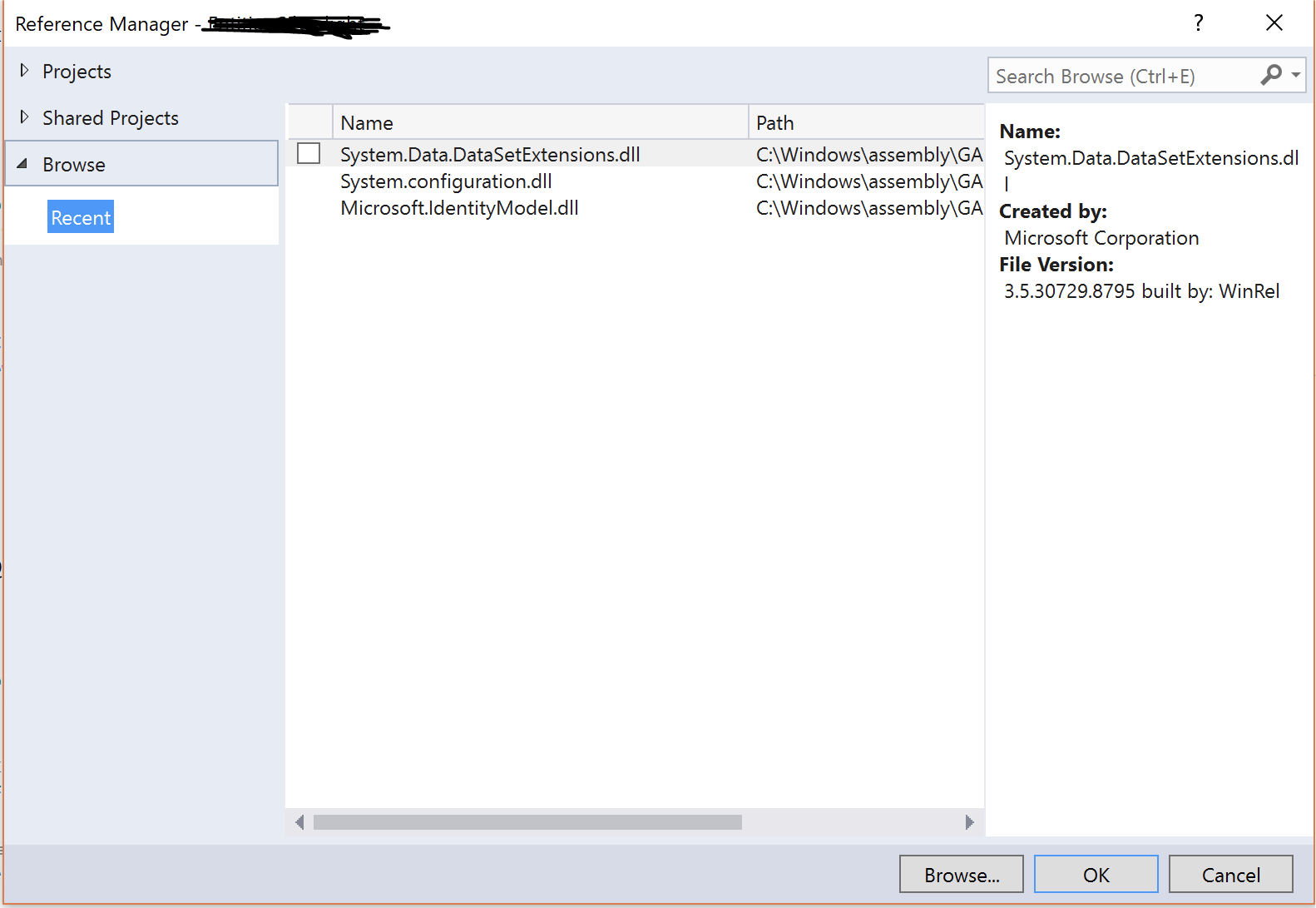

Of course, as I ran and tweaked the script I ran into some interesting challenges. Most of them have to do with referencing assemblies from the Global Assembly Cache (GAC). It seems that with the new project format we can no longer just add a reference to an assembly in the GAC from the Add Reference dialog. For example, here is the Add Reference dialog in Visual Studio 2015:  And here it is again in Visual Studio 2017 for a project using the new format:

And here it is again in Visual Studio 2017 for a project using the new format:  I do think this is a good thing since the GAC is a bit of a relic from the past, but it does make moving to the new format a bit more difficult. Luckily we can still add a reference to an assembly on disk by including the (dare I see notorious) element and pointing it at the full path to the assembly inside the GAC. However, in the old format, not every reference to an assembly has an associated element. For example, System.Data.DataSetExtensions is only referenced by name. We can still add these references to our new projects with a element and it will resolve it to an assembly on disk just fine. Definitely some MSBuild magic going on there. If the assembly reference specifies a full assembly name (including version, culture, public key token, etc.) however, it seems that the new MSBuild is unable to resolve those to a path. So I guess for these we will have to add those references back in manually to make it work. In our case this means Microsoft.IdentityModel (Windows Identity Foundation) and Microsoft.VisualStudio.QualityTools.UnitTestFramework (MSTest). There is also a big change in the new project format with respect to the AssemblyInfo.cs file. In fact, that file is now automatically generated during the compilation of the project. This is done based on properties set in the project file. If we leave the AssemblyInfo.cs in place then we get compile errors complaining about duplicate assembly level attributes. That’s why the script currently simply deletes the file, although it should probably copy what it finds there into the project file. One other thing I ran into is that sometimes you just have a file in your source control repository (whether that be Git or TFVC) that is no longer included in the project file. In the past this wouldn’t have mattered much, it would simply be ignored during compilation. But now every C# file is included by default so it does get compiled into your assembly now. That will fail of course if it depends on other code that did get deleted (like a class implementing an interface where the interface got deleted, but the class was only removed from the project file and not deleted on disk). In other cases though you might end up with more code in your assembly than what you had before. So make sure you don’t end up including source files that should have been deleted in the first place.

I do think this is a good thing since the GAC is a bit of a relic from the past, but it does make moving to the new format a bit more difficult. Luckily we can still add a reference to an assembly on disk by including the (dare I see notorious) element and pointing it at the full path to the assembly inside the GAC. However, in the old format, not every reference to an assembly has an associated element. For example, System.Data.DataSetExtensions is only referenced by name. We can still add these references to our new projects with a element and it will resolve it to an assembly on disk just fine. Definitely some MSBuild magic going on there. If the assembly reference specifies a full assembly name (including version, culture, public key token, etc.) however, it seems that the new MSBuild is unable to resolve those to a path. So I guess for these we will have to add those references back in manually to make it work. In our case this means Microsoft.IdentityModel (Windows Identity Foundation) and Microsoft.VisualStudio.QualityTools.UnitTestFramework (MSTest). There is also a big change in the new project format with respect to the AssemblyInfo.cs file. In fact, that file is now automatically generated during the compilation of the project. This is done based on properties set in the project file. If we leave the AssemblyInfo.cs in place then we get compile errors complaining about duplicate assembly level attributes. That’s why the script currently simply deletes the file, although it should probably copy what it finds there into the project file. One other thing I ran into is that sometimes you just have a file in your source control repository (whether that be Git or TFVC) that is no longer included in the project file. In the past this wouldn’t have mattered much, it would simply be ignored during compilation. But now every C# file is included by default so it does get compiled into your assembly now. That will fail of course if it depends on other code that did get deleted (like a class implementing an interface where the interface got deleted, but the class was only removed from the project file and not deleted on disk). In other cases though you might end up with more code in your assembly than what you had before. So make sure you don’t end up including source files that should have been deleted in the first place.

Conclusion

Right now, I’ve got the solution to a state where it compiles after I run the script with only some small tweaks because of assemblies referenced by their full name without an associated path (as mentioned above). I then tried to run the tests, but this failed miserably due to an error with embedded resources, which makes sense since we rely on them a lot but they don’t currently get migrated over by the script. For kicks I tried to revert the test projects back to the old format and run them again. Now they fail with a different error, but it doesn’t make much sense yet. I will post a follow up to this post if and when I get the tests to work. Obviously it isn’t an easy migration. Hopefully this will become a little bit better supported in the near future although that probably won’t happen until after Visual Studio 2017 ships. But if you want to live on the bleeding edge and don’t mind some work to get things working you’re welcome to try out my script.